Student Success in German Studies: Challenges and Opportunities in Senior Seminar

After having taught Senior Seminar for well over a decade, I have recently (and exacerbated by pandemic-induced complications) become concerned with the feasibility of the course as a capstone seminar that was once designed to be the culminating and climactic experience of the curriculum for students in the program – hence the online course platform banner “Auf zum Gipfel’ meaning “onward to the summit.” I have begun to doubt that we can do justice to ever-increasing expectations surrounding senior seminar - in one semester and perhaps even with the currently facilitated curriculum.

In view of increasingly harsh realities that we face in German Studies undergraduate programs (I am referencing internal institutional as well as external threats in the form of program cuts in feeder and peer programs, abandonment of second language requirements in large-enrollment BA degree programs like History, English, and International Business), it is an urgent need to review how we define ourselves in our discipline and within the academy and what we bring to the proverbial table as part of learners’ educational experience.

This paper reports on data from a six-year review period (2018-2023) to examine the extent to which graduating seniors in the German Studies program at Kennesaw State University (KSU) compared in specified student success measures with university peers. Metrics used stem from internal (program and departmental) reporting and institutionally generated data for the student population. In presenting contextual details and preliminary findings from the study, I conclude with concerns and considerations for future scholar-educators in German Studies and beyond.

Literature Review:

Given an at best uncertain future for German Studies and, more broadly, World Languages (Lusin et al., 2023), it seems an appropriate time to review past developments and assess present needs and circumstances in order to draft a path forward. By way of introduction, I summarize program- and discipline-specific mandates and correlative challenges and opportunities for instructors as well as learners in general before detailing circumstances for the KSU German Studies capstone experience.

The literature on capstone courses emphasizes their role in integrating and assessing undergraduate education. Hauhart and Grahe (2015) discuss conventional and innovative approaches to designing effective capstone courses, referencing student learning goals since the late 1990s that focused on developing learners’ “citizenship qualities” (191) in experiential learning opportunities; citing examples of course content with an overview of the history of the academic discipline in the US (182); and noting that the most common format is a discipline-specific and research-based seminar. The authors highlight the capstone course’s function in program assessment as they specifically addresses how capstone courses serve as a tool for both direct and indirect assessment methods, via summative assessments of students’ demonstrated skills and knowledge and end-term and end-curriculum student evaluations providing insights into learners’ perceptions (190). Challenges for faculty are also noted and include instructor resistance to assessment initiatives (173), underprepared and unmotivated learners (194), and accreditation requirements that mandate evidence of attained student and program outcomes (173). In describing components of an ideal capstone course, the authors advocate for appropriate prerequisites of at least one course introducing research methods to “reduce the number of underprepared students who stumble when encountering a thesis or research-based capstone.” (194) They also stress the importance of incorporating “appropriate supplemental activities into the capstone course…. to permit students to work toward that goal in stages.” (194) As instructors are well-advised to guide students in selecting topics for research (195), they are also encouraged to offer students as much choice as possible while ensuring appropriate task sequencing and task timelines (195) and regular review (196). For the management of challenging students, they recommend addressing “instances of weak preparation and poor motivation aggressively when they arise.” (197) In turn, adopting methods to incentivize and reward high-achieving students with extra-curricular opportunities such as conference presentations or publications (197), or in research-based experiences (Kistner et al., 2021) may prove appropriate.

Christ (2007) introduces his resource handbook by noting the twofold pressures faculty face: “Simply stated, faculty do assessment for either internal or external reasons.” (4) He describes the discussions on assessment in light of off-campus mandates focused on accountability (5) and student learning environments (8). Additionally, he recognizes internal pressures and reasons for program and course assessments originating with administrators, faculty, and students (10). In his chapter, Moore (2007) emphasizes the capstone course's role as the ideal context for direct and summative assessment within the curriculum: “In a summative evaluation of the students' experience in the university curriculum, a capstone course is an instrument used to directly assess the performance of students in the attainment of institutional and departmental curricular expectations.…. The capstone course may be the singular opportunity to determine if the student has assimilated the various goals of his or her total education.” (439)

The authors above summarize research of several decades that argues the merits and recognizes the challenges of the capstone undergraduate course. They recommend strategies to mitigate evident issues and advocate for the course as the appropriate platform for summative assessment of students’ qualifications as well as evaluation of learners’ perceptions.

The German Studies Program and Capstone Experience at KSU:

As noted above, German Studies at KSU replicates a general nation-wide trend of declining program enrollment, but also faces program closings at high schools in our state and county, from which we predominantly draw students (KSU, 2023).

Additionally, internal institutional threats at KSU include that large-enrollment disciplines recently eliminated or reduced the second-language requirement; and, that learners’ choice of courses that are non-essential to the Major are disincentivized since such non-essential courses may not qualify for federal financial aid or other funding. These policy changes are rooted, arguably, in the push to graduate students faster, with learners completing their education more efficiently and without being sidetracked in costly explorations of unrelated studies.

However, at KSU, as in many undergraduate institutions, learners are feeling the burden of increasing educational costs while also juggling mandatory courseloads and employment obligations (AAUP, 2017; St. Armour, 2021; NCES, 2022). Approx. 80% of KSU students have at least a part-time job, and more than 60% of our student body have more than part-time employment.

KSU, rated as an R2 institution (doctoral degree granting university with high research activity), is the third largest university in the state of GA with approx. 45,000 students. We have the largest WLC department in the peer group of seven sister institutions in Georgia (GA) and offer Asian Studies and five language options in the BA degree program, nine language Minors and typically teach thirteen languages per semester.

The three department-wide student learning outcomes for our programs in the five languages of the BA degree also apply to German Studies:

• Language Proficiency: Students demonstrate high proficiency in the target language by communicating effectively in presentational, interpersonal, and interpretive modes in both oral and written discourse.

• Cultural Understanding: Students demonstrate an understanding of the (literary and cultural) products, practices, and perspectives of the target cultures and the connections among them.

• Professional Skills: Students demonstrate critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving abilities through task-based language activities (i.e., oral presentations, summaries, research papers, creative videos, curriculum vitae, internship reports, etc.)

The discipline- and program-specific mandates for the Senior Seminar in German Studies are, evidently, curriculum-driven, and in our case, as in increasingly more departments of World Languages and Cultures (WLC), German Studies is bound to the same curriculum as the other four major languages. While the curriculum is currently under review and requirements are reduced to offer students more flexibility, current standards include that learners must have completed at least 6 weeks of study abroad in the target culture and must have completed all course prerequisites prior to enrollment in the capstone seminar. As part of the capstone course, students complete a semester-long series of tasks and assignments (typically 5 papers) that culminate in the 10-12 pages research paper with proper documentation, an oral presentation of min. 10-15 minutes with a subsequent Q&A period (for extemporaneous speaking). Additionally, degree candidates are required to take the external assessment of the ACTFL OPIc (ACTFL, 2006) with the aspirational goal of securing a rating of Advanced Low (CEFR for speaking B.2.1).

Department-wide standards and mandates for the course are thus minimal. The only obligatory internal evaluation tool for all senior seminar instructors and for faculty members attending the senior seminar capstone presentations are likert-scale instruments for presentational speaking and for content assessment of both the paper and the presentation (focused on critical thinking) with options for open comments.

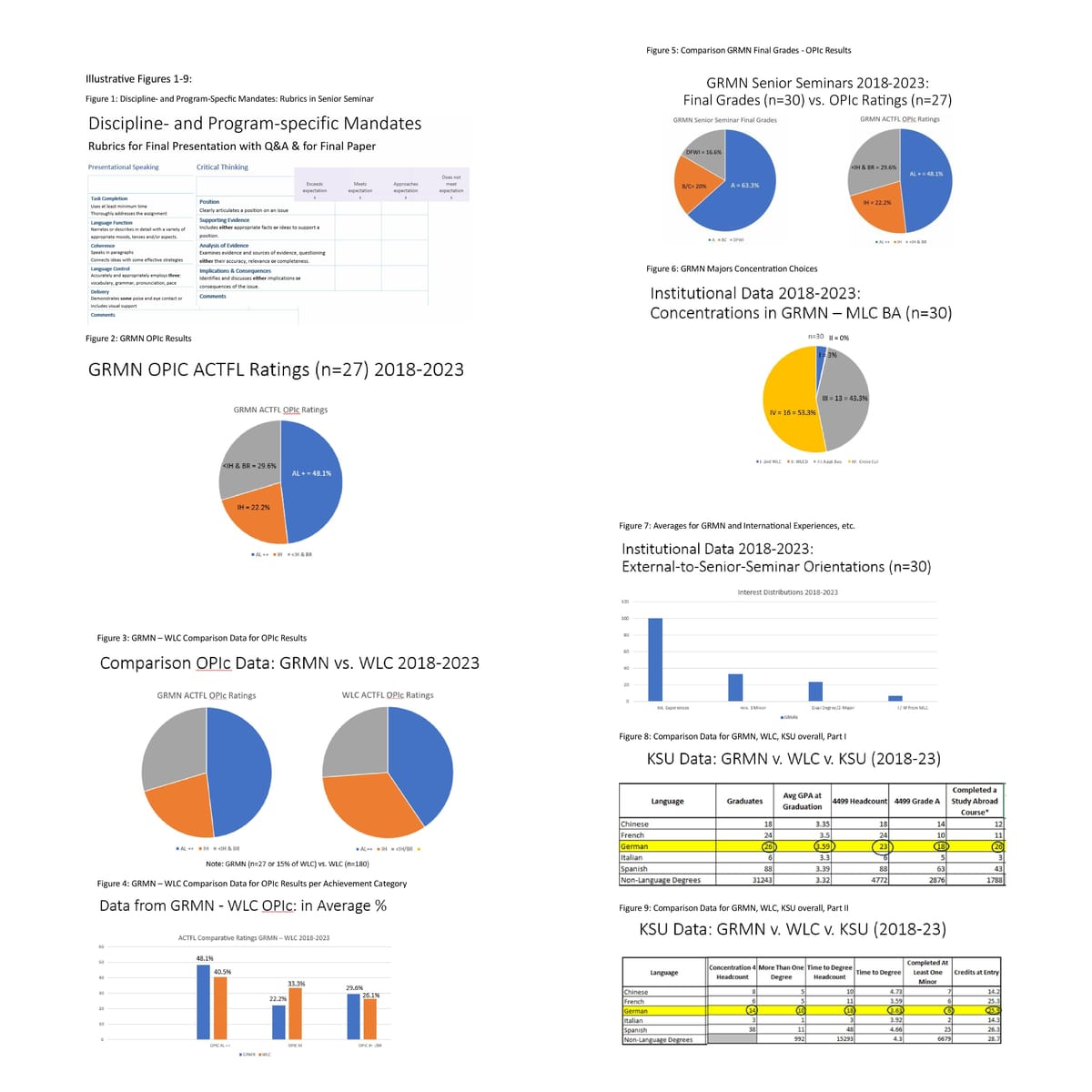

Figure 1: Discipline- and Program-Specfic Mandates: Rubrics in Senior Seminar

Evidently, a lot of trust is placed with each course instructor to design course content and facilitation, including assignments and assessments according to their expertise and level of commitment.

Based on more than a decade of having either taught or observed senior seminar students, I identify the following correlative challenges and opportunities as both content-related and facilitation-related. Content-related issues include varying expectations for skills-based assignments and assessments that both meet and go beyond discipline-specific proficiencies in language and culture, i.e. the five skills in German language and culture (reading, writing, speaking, listening and cultural understanding) in all modes of communication; and intercultural and interdisciplinary competencies in line with the ACTFL 21st century skills map for career readiness or NACE competencies, e.g., technology and media literacy, teamwork and professionalism, etc.. Additionally, there are expectations for demonstrating competence in multiple literacies related to German language, literature, and culture.

At our institution (including, and beyond German Studies), capstone courses are often taught as faculty overload and attended by a small group of students with varying interests and levels of preparation, as well as personal-professional skills (incl. time management; learner-driven research). Hence course content design as well as course facilitation require initiative and flexibility from both sides, the instructor and the learner. In the best-case scenario, the course attendees work consistently and with little supervision or only minor, individuated guidance according to directions provided, i.e. they are students who are ready to complete academically rigorous tasks and pursue independent research connected to further academic or career goals. But at the opposite end of the spectrum are the scenarios in which the instructor scrambles to develop or advance sometimes basic skills and knowledges to reach program mandates (such as how to structure a research paper, cite sources, incorporate quotations, etc.). In such cases, faculty and learners scramble to attain the course goals, rendering what was intended to be a thrilling ascent to a climactic experience a not-so-pleasant arduous and exhausting obstacle course. Frankly, in recent semesters, the latter has become the more frequent, and even the predominant experience, and not the exception.

In what follows, I seek to complement my professional observations by reporting on institutional data for the past six years (spring 2018 – spring 2023) in an effort to answer the question: How do our German Studies graduates “do” and compare to peers in other languages and disciplines?

Reviewing the Data: KSU German Studies in Context

The data pool for this study consists of a sample of 30 German Studies (GRMN) Senior Seminar participants, 180 WLC Senior Seminar students, and 31,243 KSU undergraduate graduates.

For the GRMN and WLC degree graduates, I report on internal departmental records of the external assessment, i.e., the ACTFL OPIc results in comparison to the end-course, instructor-assigned final grade. For GRMN, WLC, and non-WLC KSU graduates, I draw from institutionally generated data to triangulate the findings and provide comparison data for student success measures as reflected in, e.g., time to degree-completion, GPA at graduation, academic interests, etc..

Figure 2: GRMN OPIc Results

In Figure 2, the sample for OPIc results (n=27) reflects that among the total of 30 enrollees in senior seminar, only 27 completed the course and the OPIc. It is noteworthy that the completion attrition amounts to 10% of the sample. Among those who completed the requirements, 13 of 27 or 48.1% met or exceeded the aspirational mandate of an ACTFL Advanced Low rating; two students earned a rating of Advanced Mid. However, a combined total of twelve participants fell short of expectations – with six (or 22.2%) reaching Intermediate High and eight (or almost 30%) scoring lower than Internmediate High.

Figure 3: GRMN – WLC Comparison Data for OPIc Results

Figure 3 compares German Studies data with data from peers in the four other WLC Major languages (Chinese, French, Italian, Spanish). German learners present slightly better in the category of meeting or exceeding expectations, i.e. having attained a rating of Advanced Low or better. By contrast, German Studies seniors also have a slightly larger representation of not meeting expectations (scoring under Intermediate High, or not getting a rating – visualized in grey), or of approaching expectations (a rating of Intermediate High, illustrated here in orange). Figure 4 visualizes the same data in a bar graph for easier comparison:

Figure 4: GRMN – WLC Comparison Data for OPIc Results per Achievement Category

The German sample of 27 students compares notably to the total WLC sample of 180 graduates as 15% during the review period of 2018-2023. And, while the largest WLC student group consists of Spanish majors (which includes a heritage and native speaker demographic), the WLC student sample also includes Chinese graduates for which the aspirational OPIc score is Intermediate High.

To provide further context, I juxtapose ACTFL OPIc scores with KSU-generated data on seven variables for the study period. The categories include averages of (1) final course grades, (2) MLC-Concentration choices, (3) learners’ international experiences, (4) completion of additional academic Minors, or double Majors/dual degrees, (5) average time-to-degree, (6) prior-to-entry credit hours, and (7) overall (institutional) grade point average (GPA).

Figure 5 shows how the external evaluation of the ACTFL OPIc compared to internal instructor-assigned final course grades for senior seminar completion.

Figure 5: Comparison GRMN Final Grades - OPIc Results

Noteworthy for the category of GRMN final grades is the high percentile of the letter grade A, which 19 of 30 learners (63.3%) attained. Taking together the remaining passing grades of B and C, a total of six (20%) of the students approached expectations. The DWFI rate in the course during the review period totals five students or 16.6%.

In comparing the results for GRMN final grades with GRMN OPIc results, it is evident that only the segment of “approaching expectations” (grades of B/C and OPIc score of Intermediate High) are mostly congruent. Comparatively divergent are the results at each end of the spectrum: The percentile of graduates with the final grade A (63%) significantly supersedes the percentile of OPIc ratings at Advanced Low or higher (48%), i.e., the equivalent of meeting or exceeding expectations. Similarly, the results for not meeting expectations, i.e., the DWFI grades and OPIc ratings below Intermediate High present at merely 16.6% compared to almost 30%. These data document that German Studies students score significantly better in final grades given by their instructor than in the external assessment of the OPIc.

Figure 6: GRMN Majors Concentration Choices

In terms of our students’ corellative interests and potential professional or career goals, KSU institutional data show in Figure 6 that most German Studies Majors have identifiable preferences for concentrations: More than half of the graduates selected IV. Cross-Cultural Perspectives (53.3%), which is also the concentration that allows for the greatest flexibility in course choices. More than 43% of the students opted for III. Applied Business, as a very obvious interest for German Studies enrollees. Notably, none of the German Studies graduates completed the concentration II. WLED, i.e. teacher education in German in K-12. Only 10% of the students registered for concentration I. a seond language; however, Figure 6 does not reflect that a number of graduates had chosen an additional language as an academic minor (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Averages for GRMN and International Experiences, etc.

Institutional data reflected in Figure 7 communicate German Studies graduates’ ancillary interests and activities. They confirm that all graduates (or 100%) completed the program requirement of study abroad (although some students enrolled in a virtual experience during the pandemic); data obtained verfiy that some graduates had multiple international experiences (the average for this category totals 1.6 experiences per person). A notable data point is that a third of the German learners (i.e., ten individuals) completed at least one academic Minor - in addition to the required concentration as part of the degree program. Furthermore, almost a quarter of German Studies graduates finished the program with a Dual Degree/Double Major (i.e. seven learners, or 23.3%). Lastly, two students (or 6.6%) did not finish the degree.

Comparative data for GRMN, WLC, and non-WLC KSU students are displayed in Figures 8-9. They provide corroborating evidence on indicators of student success via data on average GPA at graduation, final grade for Senior Seminar, international experiences, academic interests, and completion times.

Figure 8: Comparison Data for GRMN, WLC, KSU overall, Part I

The institutionally generated KSU data show divergent numbers for GRMN graduates because (a) some dual degree graduates or double majors were not counted in the WLC but in the peer department, and (b) some graduates took the German Studies senior seminar as a differently coded course during a study abroad experience. Similarly, the total number of 162 WLC graduates deviates from our internal records of the sample size (n=180) for the review period.

The data reported in Figure 8 document the following: The KSU German Studies program has the 2nd highest number of graduates within the WLC department, after Spanish. With an average GPA of 3.59, German graduates have a higher GPA than peers in WLC and at KSU overall. Among GRMN graduates documented, a total of 18 (or 72%) finished with an A, which is the second-lowest rating within WLC (French shows the lowest with 41.6%), and higher than the figure for KSU overall, i.e. 2,876 of 4,772 non-WLC graduates (or 60 %). As mentioned above, all German graduates (or 100%) completed a study abroad course, which is the highest ratio within WLC, followed by 66.6% of Chinese graduates. By comparison, only 1,788 of the more than thirty thousand non-WLC KSU students (or 5.7%) participated in a study abroad experience.

Figure 9: Comparison Data for GRMN, WLC, KSU overall, Part II

The data in Figure 9 confirm the internally generated findings for GRMN learners choices among concentrations: “Cross-Cultural Perspectives” ranks highest with 53.8% of German graduates - while the lowest percentile is held by French learners, i.e., 25%. Also, German learners have the highest percentage of holding more than one degree at 38.5% (followed within WLC by Chinese students (27.8%) and compared to 3.2% of KSU students overall). German graduates are in second place for time-to-degree completion as they are listed with 3.63 years, compared to French students who finish slightly faster, i.e. in 3.59 years. As noted above, almost a quarter (23%) of German students have at least one minor (6/26), but they rank behind all other WLC graduates in this category – yet above KSU students overall (21.4%). Among all graduates, GRMN ranks 3rd for credit hours prior to entry, trailing Spanish learners and KSU students overall.

Conclusion:

Internal German Studies program data and institutionally generated data for German Studies in comparison to WLC and non-WLC KSU graduates suggest the following overall findings: (1) Compared to WLC and KSU students, graduates in German Studies start and finish strong, as indicated by the high average of credit hours prior to entry and the high average GPA at graduation, as well as by high scores in the Senior Seminar final grade and the ACTFL OPIc ratings. (2) GRMN learners complete the curriculum faster than most of their peers (with the exception of French learners) despite having taken advantage of additional academic opportunities and experiences (by opting for a second major, a minor, and by participating in study abroad experiences).

The following limitations and consideration merit mention: Despite efforts at triangulating data from institutional sources, the sample sizes for German Studies are small and prevent generalizable conclusions; further study is needed to account for divergences for data points and to obtain additional insights into remaining questions (see below).

However, an observation on the discrepancy between OPIc results and the instructor-generated final course grades in Senior Seminar may be admissible: In the capstone seminar, the final grade is, department-wide, based on a number of oral and written assignments throughout the semester, wheras the OPIc score is based on a student’s extemporaneous communication skills shared in a fairly brief recording; hence it is not surprising that the OPIc ratings present, on average, lower than the course final grades. It has been my experience that appropriate strategic preparation for the OPIc as an integrated component of Senior Seminar has helped GRMN learners to attain the aspirational goal of Advanced Low; however, not all faculty who taught the capstone course were committed to coaching students for the OPIc, which remains an issue for internal discussion and problem-solving. Lastly, German Studies graduates may have received better grades in senior seminar than what the external assessment of OPIc suggests they should have received, but, on average, fewer finished with an A compared to all peers except for learners of French.

The high achievement rate of 100% participation in international experiences among GRMN students is, arguably due to the program requirement and the generous grant-funding that external foundations contributed during the review period. Participation in study abroad and credit hours prior to entry may have also contributed to the high percentage of GRMN learners with more than one degree and the reduced time-to-degree completion averages for GRMN graduates. Further study is needed to examine the extent to which financial support and program requirements may go hand in hand to advance students’ successful completion of the curriculum.

The data reviewed here do not address how well KSU graduates are prepared in the discipline- and program-specific areas of learning outcomes – although the final grades in Senior Seminar and the OPIc results may serve as reference points. Since, for WLC graduates, the goals of proficiency in all modes, cultural understanding, and professionalism and the capstone grading rubrics are described in very general terms, faculty have consistently argued for and against more specificity. Department-wide, the faculty agreed not to identify details with respect to content knowledge and cultural understanding. As in many peer programs, faculty with diverse areas of expertise prioritize their disciplinary interests in the classes they teach, including in senior seminar.

Finally, the data reviewed here do not address the challenges that instructors or students face during senior seminar with respect to expectations and perceptions of accomplishments and satisfaction. Facilitation of attitudinal surveys may be advisable to examine the extent to which both learners and educators struggle during the capstone experience.

References:

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL). (2006). ACTFL Oral Proficiency Interview - Computer (OPIc). https://www.actfl.org/assessment-professional-development/assessments-the-actfl-testing-office/oral-proficiency-interview-opi/opic

American Association of University Professors (AAUP). (2017). Recognizing the reality of working college students. AAUP. https://www.aaup.org/article/recognizing-reality-working-college-students

Hauhart, R. C., & Grahe, J. E. (2015). Designing and teaching undergraduate capstone courses. Jossey-Bass.

Kistner, K., Sparck, E. M., Liu, A., Sayson, H. W., Levis-Fitzgerald, M., & Arnold, W. (2021). Academic and professional preparedness: Outcomes of undergraduate research in the humanities, arts, and social sciences. SPUR: Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research, 4(4), 3-9. https://doi.org/10.18833/spur/4/4/1

Kennesaw State University (KSU). (2023). KSU Factbook 2023-2024: Incoming student profiles. Kennesaw State University. https://ir.kennesaw.edu/fact-book-incoming-students.php

Lusin, N., Peterson, T., Sulewski, C., & Zafer, R. (2023). Enrollments in languages other than English in US institutions of higher education, Fall 2021. Modern Language Association of America. https://www.mla.org/content/download/191324/file/Enrollments-in-Languages-Other-Than-English-in-US-Institutions-of-Higher-Education-Fall-2021.pdf

Moore, R. C. (2007). Direct measures: The capstone course. In W. G. Christ (Ed.), Assessing media education: A resource handbook for educators and administrators (pp. 439-450). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315096780

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2022). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/2022/ssa_508.pdf

St. Amour, M. (2021). Most college students work, and that's both good and bad. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/05/20/most-college-students-work-and-thats-both-good-and-bad